Understanding Mechanisms of Body Weight Stagnation

A research-referenced exploration of physiological and behavioural factors in weight regulation

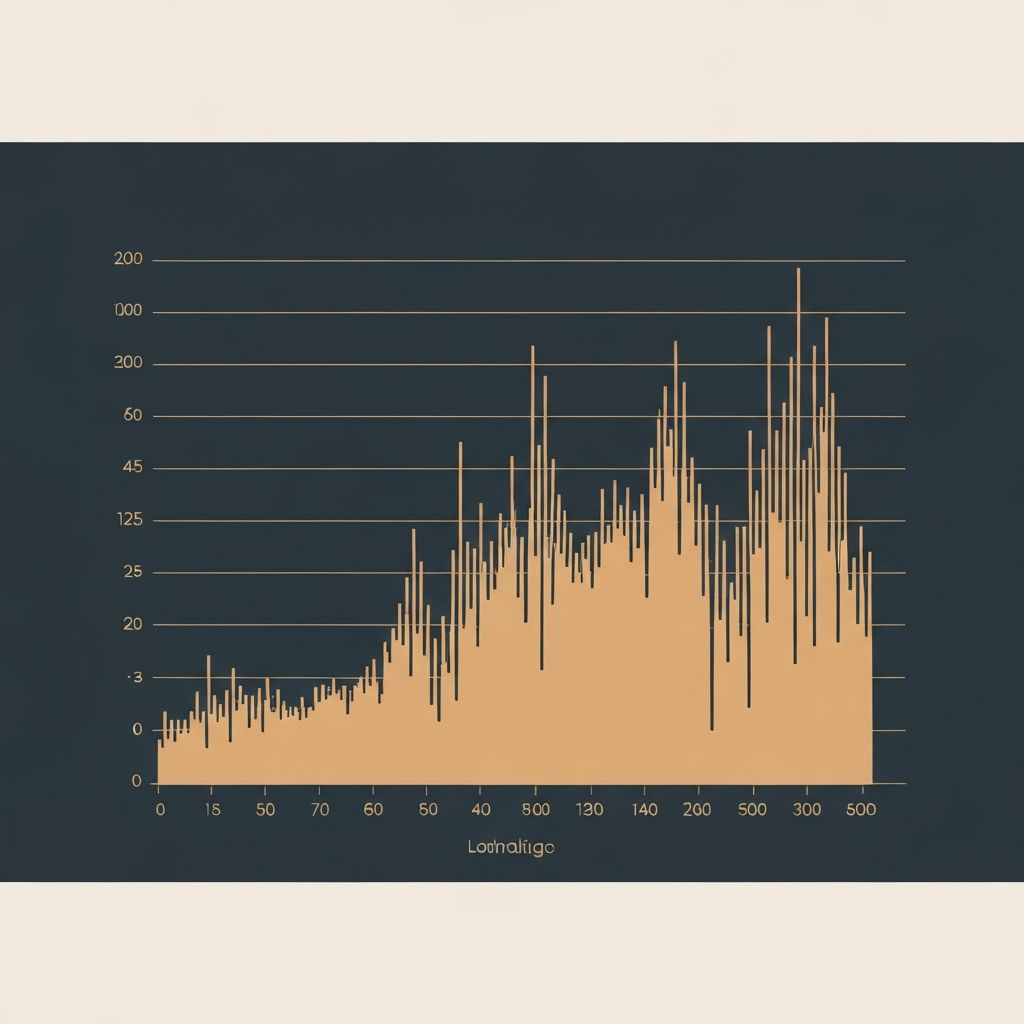

Adaptive Thermogenesis and Metabolic Down-Regulation

During sustained energy restriction, resting metabolic rate (RMR) declines beyond what body weight loss alone would predict. This adaptive thermogenesis reflects the body's homeostatic defence mechanisms.

The magnitude of metabolic suppression varies between individuals. Research from metabolic ward studies shows that the reduction typically ranges from 10–25% relative to predicted RMR losses, though individual variation is substantial.

Metabolic adaptation represents a physiological response to sustained energy deficit, not a permanent or irreversible state.

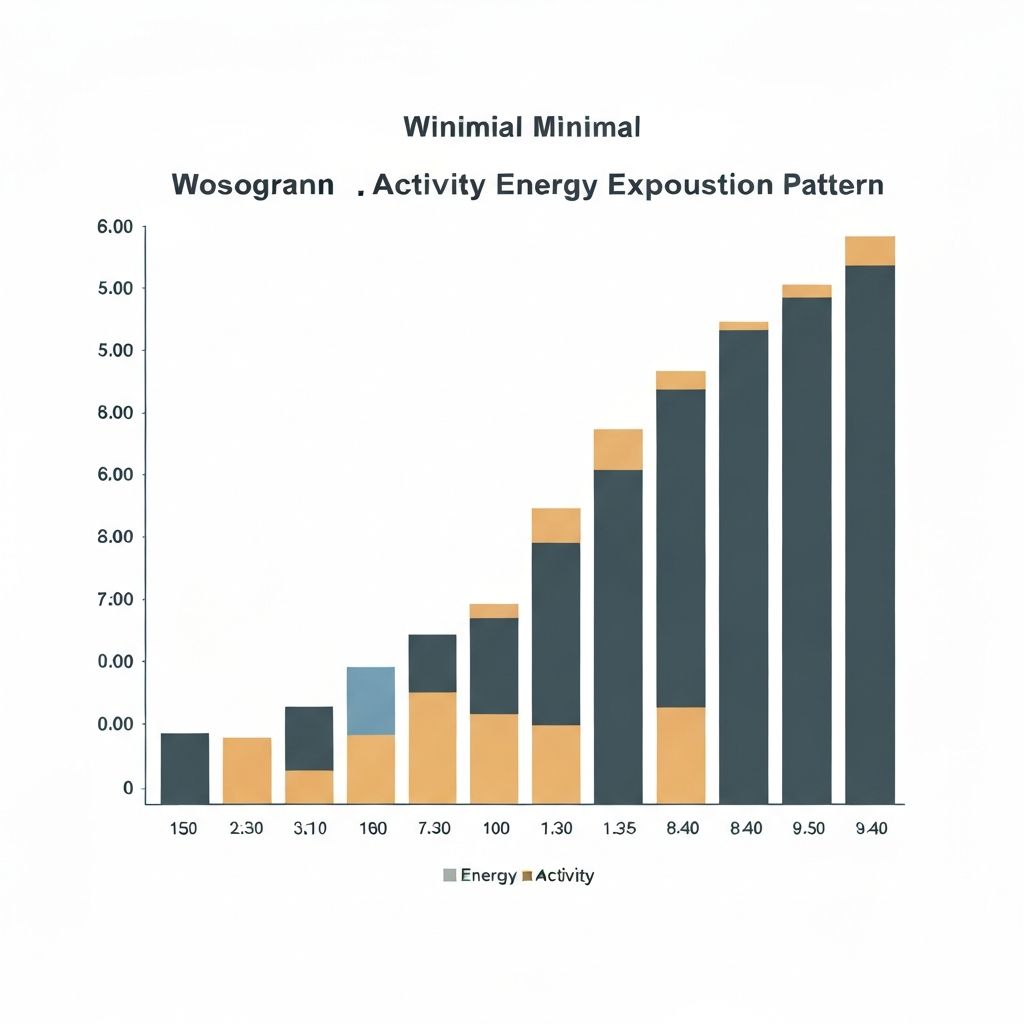

NEAT Reduction and Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis

Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) encompasses all energy expenditure outside formal exercise: occupational activity, fidgeting, postural maintenance, and daily movement patterns.

During prolonged energy restriction, NEAT can decline significantly—sometimes accounting for 15–30% of total daily energy expenditure changes. This reduction occurs both consciously (deliberate movement reduction) and unconsciously (postural and fidgeting changes).

NEAT fluctuations represent adaptive responses to sustained energy deficit and demonstrate substantial inter-individual variability.

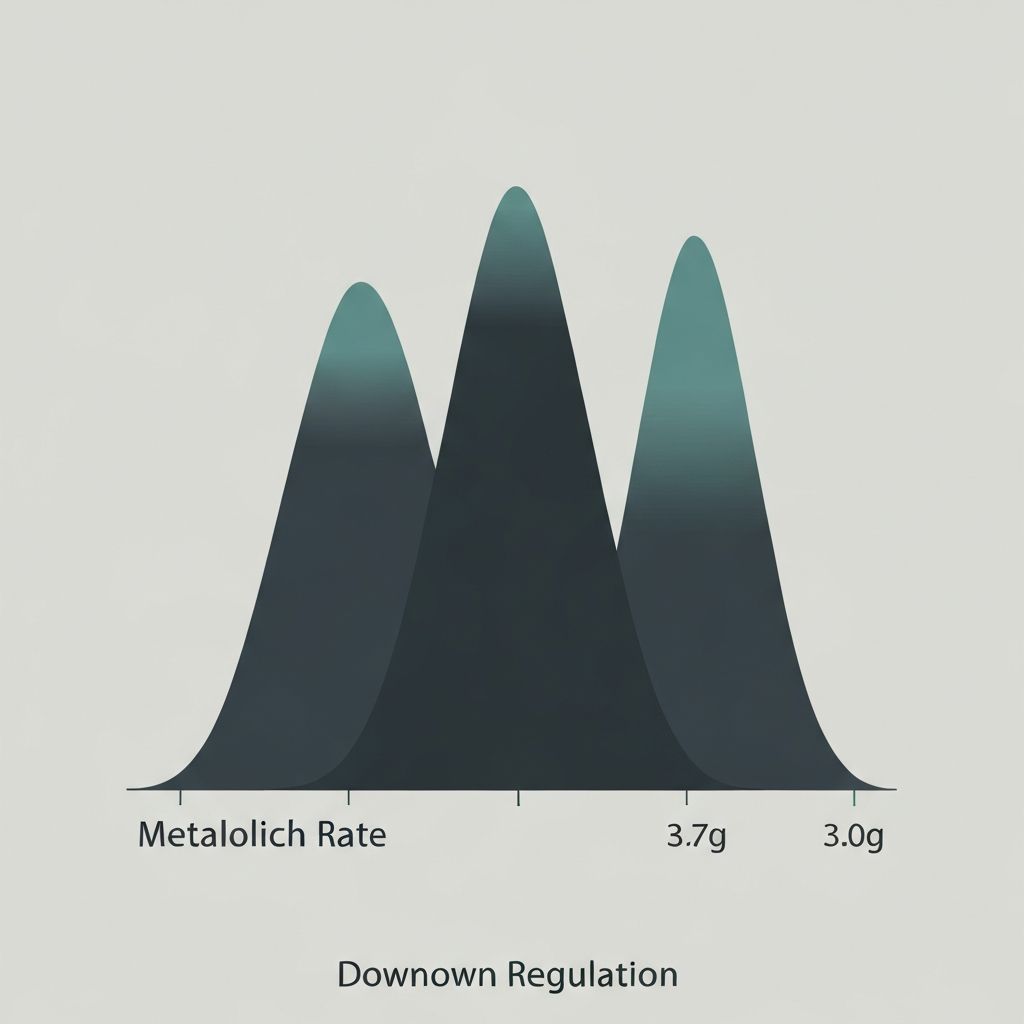

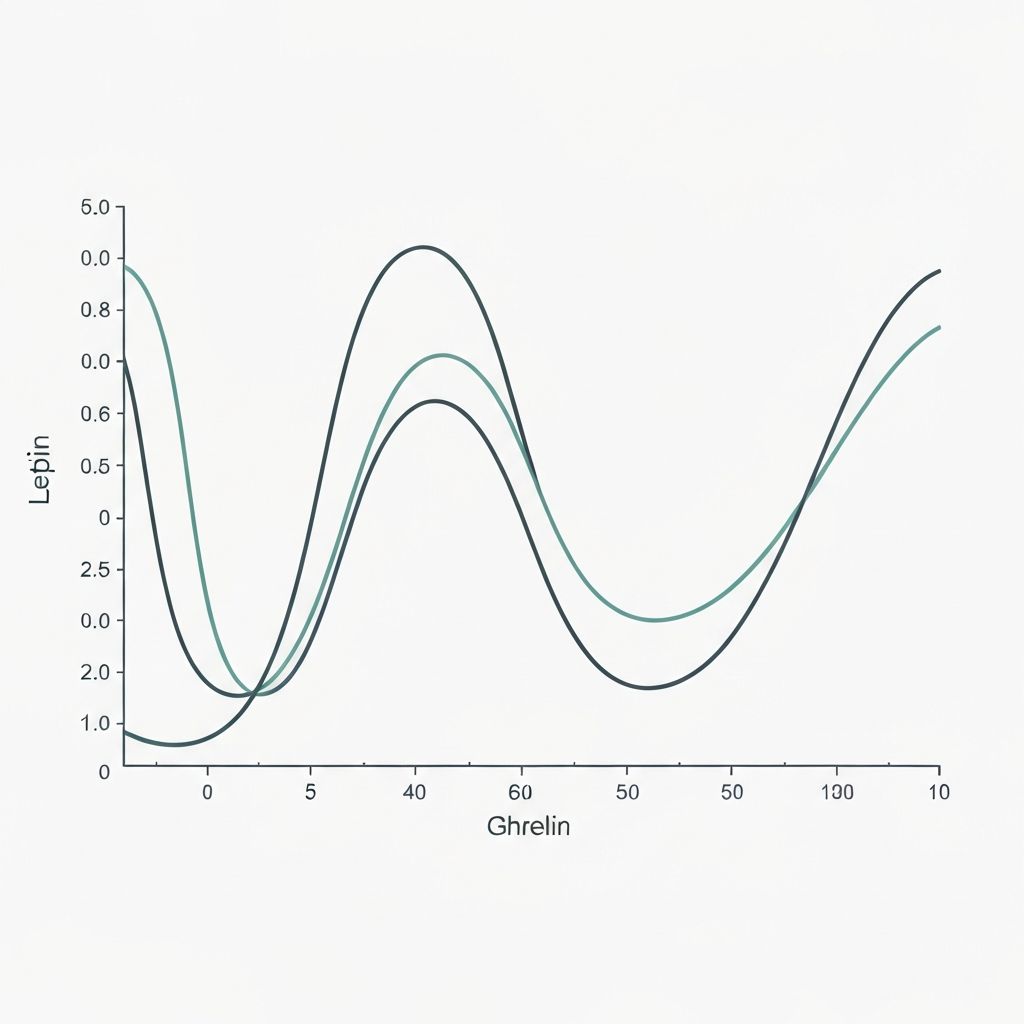

Hormonal Profile Shifts During Energy Restriction

Leptin, the primary satiety hormone, declines in proportion to fat mass loss and energy deficit severity. Ghrelin, the hunger hormone, typically rises. Cortisol may increase; insulin sensitivity can shift.

These hormonal changes reflect systemic adaptation signals that influence appetite perception, energy prioritization, and metabolic efficiency. The precise magnitude and timeline vary across individuals depending on diet composition, activity patterns, and genetic factors.

Hormonal adaptations are context-dependent and demonstrate considerable individual heterogeneity in both direction and magnitude.

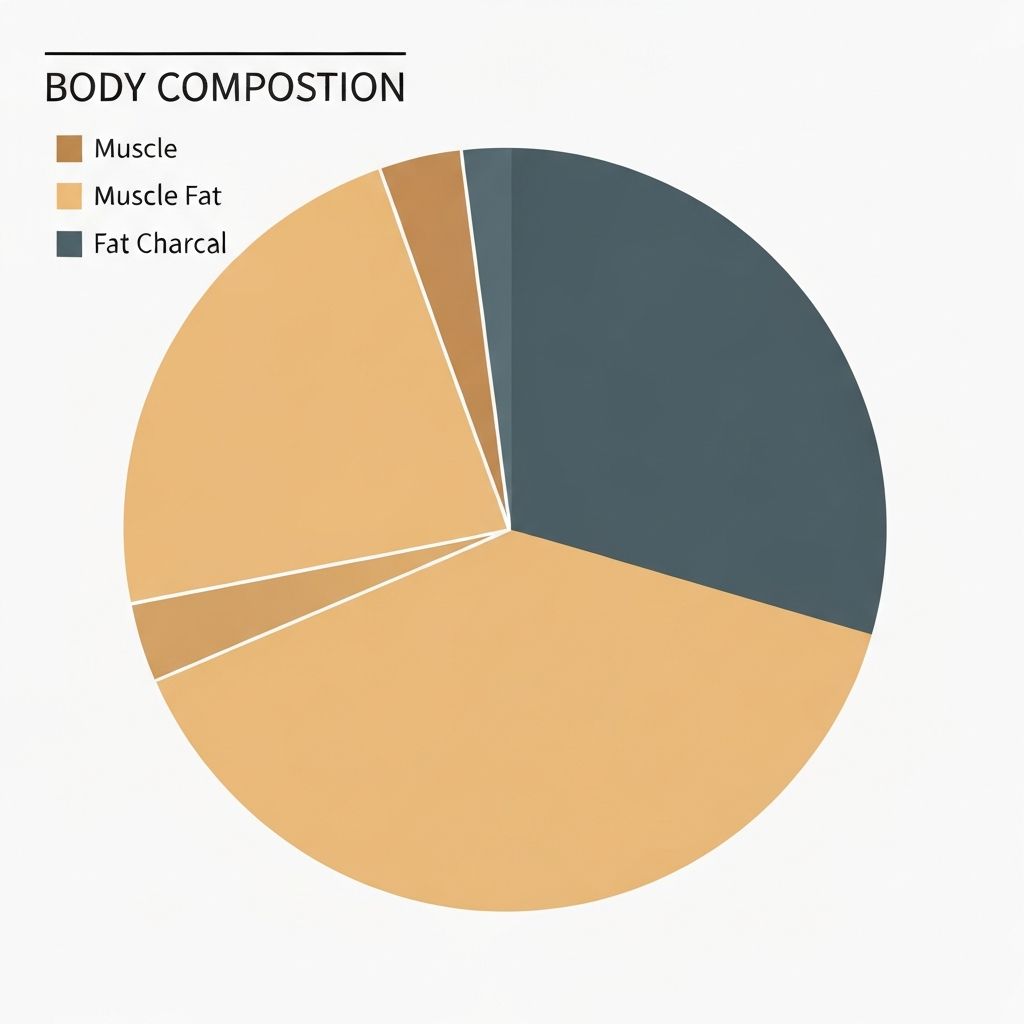

Influence of Lean Mass on Energy Expenditure

Lean body mass (muscle, organ tissue, bone) is metabolically more active than fat tissue. When total weight loss includes significant lean mass loss—which commonly occurs during energy restriction—resting metabolic rate declines more sharply.

The proportion of weight lost as lean mass versus fat mass varies based on training stimulus, protein intake, deficit magnitude, and individual genetics. Preservation of lean mass through resistance training and adequate protein may partially attenuate metabolic suppression.

Water Retention and Glycogen Fluctuations

Scale weight represents total body weight, including water, glycogen, organ contents, and gastrointestinal contents. These can fluctuate substantially independent of fat mass changes.

Glycogen depletion and repletion, sodium intake variations, hormonal cycles, training recovery status, and hydration levels all influence scale readings. Fat loss may continue while scale weight appears static due to concurrent water retention or glycogen repletion.

Scale weight fluctuations often mask underlying changes in body composition and do not necessarily reflect metabolic stagnation.

Behavioural Drift and Adherence Observations

Sustained energy restriction is cognitively and physically demanding. Over time, minor deviations in adherence accumulate: portion sizes gradually increase, meal frequency changes, food quality shifts, or tracking accuracy declines.

These behavioural patterns are not failures of willpower but predictable human responses to prolonged restriction. Observational studies of long-term weight loss show that apparent plateaus often coincide with measurable increases in energy intake relative to initial restriction levels.

Set-Point Theory and Homeostatic Defence Mechanisms

The set-point hypothesis proposes that the body defends a particular body weight through integrated physiological and behavioural mechanisms. When weight falls below this defended level, multiple systems activate to oppose further loss.

Modern understanding treats set-point as a homeostatic range rather than a fixed point, influenced by genetics, environmental factors, prior weight history, and physiological status. The theory contextualises metabolic adaptation and appetite changes as coordinated responses rather than independent phenomena.

Research Observations Summary

Metabolic ward studies—where food intake and activity are precisely controlled—show consistent metabolic suppression during prolonged energy restriction. Long-term cohort studies document the prevalence of weight loss plateaus and their physiological correlates.

Controlled interventions comparing diet composition, macronutrient ratios, and exercise strategies reveal that outcomes vary substantially between individuals. No single factor predicts individual response magnitude.

Individual Adaptation Differences

The degree and speed of metabolic adaptation varies considerably. Some individuals show minimal suppression; others show substantial changes. Factors contributing to this variability include baseline metabolic rate, prior weight loss history, genetic predisposition, diet composition, exercise modality, sleep quality, and stress levels.

Age, sex, and hormonal status also influence adaptation responses. Understanding that individuals are not uniform in their physiological responses is essential to contextualising observed variation in weight loss trajectories.

In-Depth Analyses

Physiological Basis of Adaptive Thermogenesis

Detailed exploration of metabolic rate regulation, mitochondrial efficiency changes, and hormonal signalling during energy deficit.

Read article →

Changes in Non-Exercise Activity Over Time

Comprehensive analysis of how daily activity patterns shift during sustained restriction and the measurement challenges involved.

Read article →

Hormonal Adaptations During Energy Restriction

Detailed hormonal cascade responses to sustained deficit including leptin, ghrelin, and cortisol dynamics.

Read article →

Lean Mass Influence on Energy Expenditure

Exploration of how body composition changes affect metabolic rate and the role of resistance training in preservation.

Read article →

Behavioural Factors in Apparent Stagnation

Analysis of adherence patterns, portion drift, and dietary compliance changes across long-term restriction periods.

Read article →

Individual Variability in Weight Regulation

Comprehensive overview of inter-individual differences in metabolic adaptation, genetic factors, and response heterogeneity.

Read article →Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly is metabolic adaptation?

+Metabolic adaptation refers to the decrease in resting metabolic rate that occurs during sustained energy restriction, beyond what would be predicted from body weight loss alone. It represents a physiological response to perceived energy scarcity and is mediated by hormonal and neural systems.

Is a weight loss plateau permanent?

+No. A plateau represents a temporary state where weight loss has slowed, not a permanent cessation of fat loss. Continued energy deficit—whether achieved through further dietary adjustment or increased activity—typically results in renewed weight loss, though the rate varies individually.

How much does metabolic rate actually decrease?

+The magnitude varies considerably between individuals. Research suggests metabolic suppression ranges from approximately 10–25% relative to predicted losses, depending on deficit severity, duration, diet composition, exercise patterns, and individual genetics. Some individuals show minimal adaptation; others show substantial changes.

Does metabolic adaptation mean fat loss has stopped?

+No. Metabolic adaptation slows fat loss rate but does not halt it entirely. An energy deficit, regardless of magnitude, continues to result in fat loss. The rate is slower than initially observed, but the process continues. Scale weight may mask this due to water retention or glycogen fluctuations.

What role does NEAT play in weight loss plateaus?

+NEAT (Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis) comprises daily movement, occupational activity, and fidgeting. During sustained restriction, NEAT can decline 15–30%, representing substantial energy expenditure reduction independent of intentional exercise. This contributes to apparent stagnation but is a measurable, physiological phenomenon.

How does lean mass loss affect metabolic rate?

+Lean mass (muscle, organs, bone) is metabolically more active than fat tissue. Weight loss that includes significant lean mass loss produces greater metabolic suppression than fat-preferential loss. Resistance training and adequate protein intake may help preserve lean mass during energy deficit.

Why does scale weight fluctuate without fat loss changes?

+Scale weight includes water, glycogen, organs, gastrointestinal contents, and waste products in addition to fat mass. Sodium intake, hydration status, hormonal cycles, training recovery status, and glycogen depletion/repletion all cause fluctuations independent of actual fat mass changes.

What is the set-point theory?

+The set-point hypothesis proposes that the body defends a particular body weight or range through integrated physiological and behavioural mechanisms. Modern understanding treats it as a homeostatic range rather than a fixed point, influenced by genetics, environment, prior weight history, and current physiological status.

How do hormones change during energy restriction?

+Leptin (satiety hormone) declines proportionally to fat loss. Ghrelin (hunger hormone) rises. Cortisol may increase. Thyroid hormones may decline. These changes reflect coordinated physiological responses to sustained deficit and influence appetite, energy prioritization, and metabolic efficiency.

Does adherence drift contribute to plateaus?

+Yes. Observational studies show that apparent weight loss plateaus frequently coincide with measurable increases in energy intake relative to initial restriction levels. Portion sizes drift upward, meal frequency changes, or tracking accuracy declines. These are predictable responses to sustained cognitive and physical restriction demands.

Why do different people respond differently to energy restriction?

+Individual variation in metabolic adaptation, NEAT reduction, lean mass preservation, and behavioural adherence is substantial. Contributing factors include baseline metabolism, prior weight history, age, sex, genetic predisposition, diet composition, exercise modality, sleep quality, and stress levels. No single factor predicts individual response.

Is there research evidence for these mechanisms?

+Yes. Metabolic ward studies (precisely controlled food and activity) consistently document metabolic suppression. Long-term cohort studies show plateau prevalence and physiological correlates. Controlled interventions reveal substantial inter-individual variation in outcomes. This information is synthesised from peer-reviewed research spanning several decades.

Continue Exploring Metabolic Regulation Topics

This resource presents research-referenced information about weight regulation mechanisms. For detailed mechanistic discussions, personal application guidance, or specific circumstances, explore our in-depth articles.

View All Articles